Maryland’s landmark heat stress standard risks leaving farmworkers behind as temperatures and political tensions rise

The following article was published on Medium’s Dialogue & Discourse on May 16, 2025.

In April 20204, farmworkers load watermelons harvested that day from a tractor into the warehouse for processing in Hurlock, Maryland, on the Eastern Shore. Photo: Alisha Camacho, RESPIRAR

Even at 5 p.m. in early October, the sun beat down on a group of men harvesting watermelons in Hurlock, Maryland. With no breeze or a cloud in sight, “It was brutal,” said Stephanie Hernandez, who oversees our outreach efforts for the RESPIRAR Project.

Hernandez has interacted with farmworkers participating in our research project, RESPIRAR, since April 2023. The goal of RESPIRAR is to understand the complexity of the agricultural system and its connection to disparities in respiratory health among migrant and seasonal farmworkers. The motivation for RESPIRAR is the disproportionate impact the coronavirus pandemic had on migrant and seasonal farmworkers.

Willing participants complete housing assessment surveys and provide nasal swabs tested for coronavirus variants, respiratory syncytial virus and influenza. Positive results prompt internal procedures notifying workers.

This evening, Hernandez was wrapping up two years of fieldwork. As she waited for the men to take a break to collect nasal swabs, she observed them laboring under the sun, moving quickly as they skillfully hoisted 20- to 50-pound watermelons down an assembly line into a tractor bed.

“How do you manage in this heat?” Hernandez asked in Spanish. “Do you get breaks?”

One worker, granted anonymity, said they rest when the tractor heads to the warehouse. “They grab a watermelon, sit on it, and wait,” Hernandez translated. “No shade, no cover. Just sitting under the sun, trying to catch their breath.”

Farmworkers harvest watermelons in Hurlock, Maryland, on the Eastern Shore in October 2024. Photo: Stephanie Hernandez, RESPIRAR

News of Maryland’s landmark heat stress standard, enacted just a week earlier, hadn’t reached the fields yet. Even if it had, the law only requires action when the heat index reaches 80°F. That evening, the reading hovered around 70°F but felt closer to 85°F. When indirect sunlight, the real feel can add 15 degrees to the heat index value.

This moment illustrates one of the rule’s shortcomings: in practice, employers have discretion over whether to implement safety protocols when temperatures fall below the threshold, even when the real feel is higher. Based on research conducted before the rule was enacted, we believe employers are unlikely to follow these guidelines voluntarily. And without strong enforcement mechanisms in place, many farmworkers will remain hesitant to take breaks due to cultural barriers, employer dependency and fear of retaliation.

When Maryland passed its heat stress standard, we recognized gaps in the rule that could limit its effectiveness. Sharing our findings is a core part of the study as we aim to support policies and best practices to improve working conditions.

A Law with Good Intentions

Maryland is the first East Coast state to adopt a heat stress standard, joining a handful of others nationwide, including California and Oregon. Passed after the death of Baltimore City employee Ronald Silver II, who collapsed on the job due to extreme heat last August, the law was praised as a “common sense plan” by Maryland Labor Secretary Portia Wu.

The standard requires employers to provide water, shade and rest when the heat index exceeds 80°F, with additional protections triggered at 90°F and 100°F. Employers must also train workers to recognize and respond to signs of heat-related illnesses.

RESPIRAR community advisor Debbie Berkowitz, a nationally recognized worker safety and health policy advocate, commended Maryland Gov. Wes Moore for prioritizing the measure. His administration “got down to work, and in less than a year, they did it,” Berkowitz said. “It’s easy peasy. It’s not expensive. And it saves lives.”

And while we agree that the policy is a step forward, we also recognize that well-meaning laws can falter when they overlook real-world complexities. H-2A workers, who lack health insurance and stay in isolated areas, are particularly at risk.

At a November summit introducing the new standard, Rosemary Sokas, a Georgetown University professor of human science and family medicine, emphasized that any increase in temperature correlates with a rise in traumatic injuries. Agricultural workers, she said, are disproportionately affected compared to other industries like construction.

With climate models projecting longer and hotter summers in Maryland, the urgency to protect workers grows.

A Changing Climate and a Marginalized Workforce

Extreme heat is already the deadliest weather-related hazard in the U.S., according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Yet heat-related injuries and deaths are also underreported, making it difficult to understand the full scope of the threat.

“Assume heat is a contributing factor if you don’t know otherwise,” advised Cristina Campbell Harris of Maryland Occupational Safety and Health (MOSH). Especially once the heat index reaches 80°F, she added, while presenting at a virtual outreach event in April. Despite this concern, MOSH does not track heat-related illnesses and injuries as part of its performance goals.

Meanwhile, climate models forecast a surge in extreme heat days across the region. Our analysis of NOAA’s Mid-Atlantic extreme temperature data shows that places like Salisbury in Wicomico County could experience more than 50 days over 90°F by 2050. By the end of the century, nearly every summer day could reach that threshold, drastically increasing the risks for those working outdoors.

At the same time, Maryland’s reliance on migrant farm labor grows in line with national trends. From 2015 to 2023, the number of visa approvals in the state jumped 124%, based on our analysis of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services data. In 2024, the state authorized roughly 750 workers, many coming from Mexico, Haiti, and Jamaica, to support the state’s agricultural economy.

As the climate grows more dangerous for farmworkers, so do political conditions affecting them. In the face of the Trump administration’s aggressive deportation goals and continued political hostility toward immigrant communities, advocates fear that living and working conditions could worsen for this already marginalized workforce.

“All this uncertainty creates fear among immigrant communities,” said Jean-Frandy Philogene, outreach and field coordinator with the Comité de Apoyo a los Trabajadores Agrícolas, or CATA, a community organization and key RESPIRAR partner. “People are scared to go to work — or even to go outside.”

Complex Systems Need Dynamic Solutions

Maryland’s heat stress standard, like many well-intentioned policies, follows a familiar linear model: identify the problem(s), conduct research, develop and evaluate solutions. And then revise and restart the process as needed. This approach, however, often overlooks the political, financial and cultural barriers hindering real-world success.

The result? A law that looks good on paper but risks falling short in practice, especially without sufficient funding for outreach, enforcement and culturally competent training.

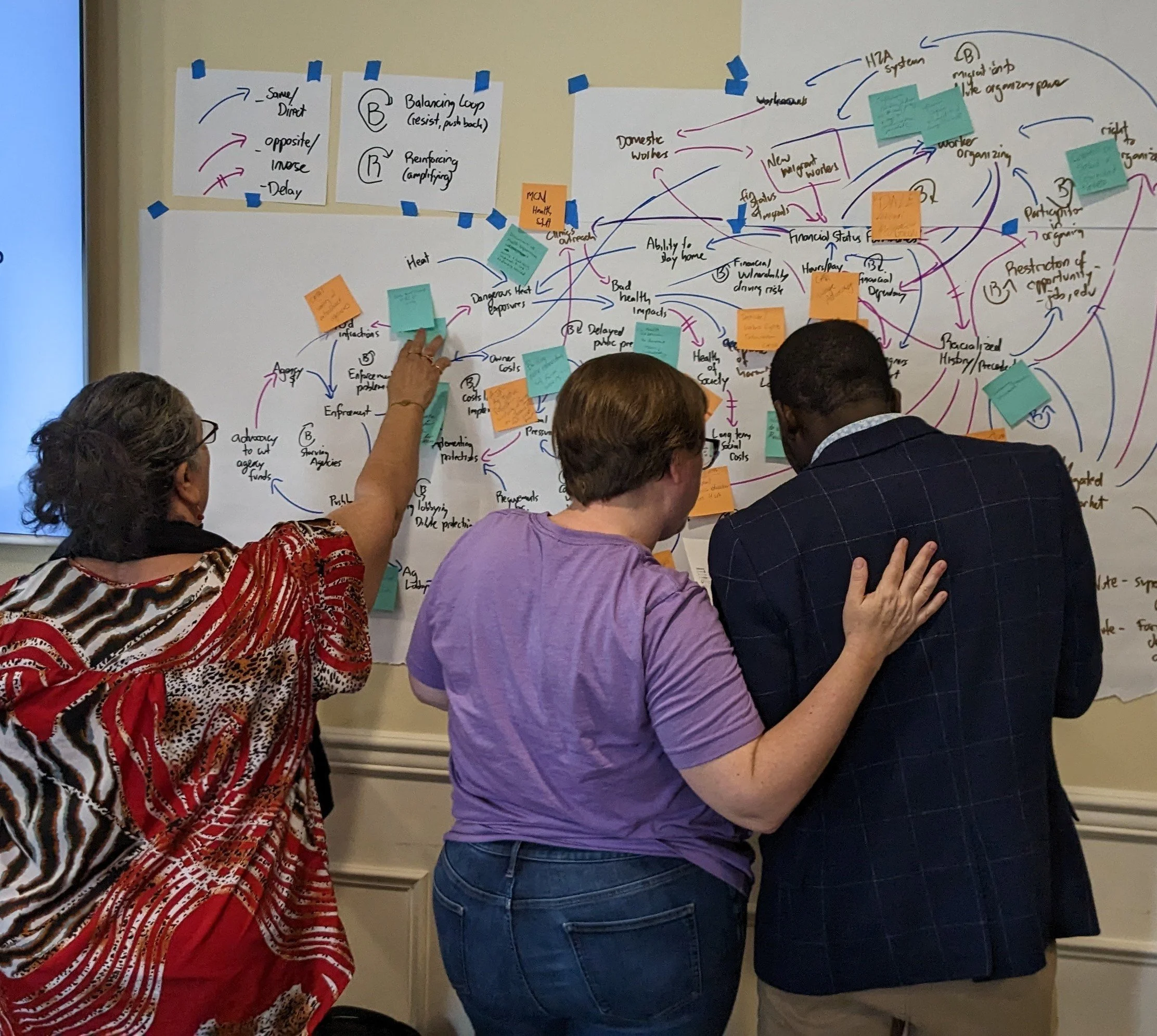

In June 2023, our systems team hosted a workshop with labor organizers, community members and researchers to identify the barriers preventing farmworkers from receiving adequate protection against heat exposure. Community-based systems dynamics, a critical component of our research, centers the perspectives and experiences of community stakeholders, while modeling how complex social systems can create unintended and sometimes unexpected behavior over time.

This heat exposure workshop also served as a training to prepare our team for designing participatory group model-building sessions with stakeholder groups. When Maryland later enacted its heat stress standard, we recognized that findings from the workshop revealed gaps that, in our view, should have been considered earlier in the policymaking process.

Team members with Comité de Apoyo a los Trabajadores Agrícolas (CATA) participate in a community-based systems dynamics heat exposure workshop in June, 2023 on the Eastern Shore. Featured from left to right: Leila Borrero Krouse, organizer & immigration specialist, Jessica Culley, general coordinator and Jean-Frandy Philogene, outreach and field coordinator. Photo: Ellis Ballard, RESPIRAR

Power Imbalances

While the standard aims to empower workers, it doesn’t address the entrenched power imbalances that often leave H-2A workers unprotected. Many avoid reporting unsafe housing or working conditions for fear of losing shifts, wages or future employment.

“There’s this sense of, oh, at any moment, we could get in trouble for things that are not bad at all,” observed Divya Aikat, one of our summer interns, reflecting on conversations with workers during site visits the following summer.

The hierarchical structure of farm labor, where crew leaders often stand between workers and farm owners, also fosters favoritism and suppresses complaints.

Logistical Barriers & Enforcement

Employers provide most workers on the Eastern Shore with housing in rural areas, leaving them without internet access or transportation. These barriers can prevent workers from receiving timely extreme heat alerts, an essential part of the new standard. The infrastructure, or lack thereof, also prevents workers from reporting violations.

These challenges underscore the importance of a strong enforcement strategy. During the November summit, Campbell Harris confirmed that MOSH was evaluating internal capacity and enforcement concerns. The agency was unable to provide an update on enforcement strategy or budget as of April.

The Cost of Toughing it Out

Even when workers want to protect themselves, cultural norms and financial pressures often take priority over health.

During the 2023 wildfire episode, our team observed farmworkers continuing to labor outdoors despite the thick smog engulfing the East Coast. This wasn’t an isolated incident. Many had also worked while ill during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic until they became bed-bound. In these high-stakes environments, taking time off can mean losing income or being replaced.

Maryland’s new heat stress standard could help change this. Employers are expected to pay workers for mandated rest breaks when they occur during normally paid working hours, Campbell Harris said at the outreach event. In theory, this guidance should help remove the financial disincentive for taking necessary breaks, but only if it’s properly enforced. Notably, the provision described is not made explicit in official state documents.

The law also requires employers to provide at least 32 ounces of water per person per hour at no additional cost. Our field team has observed workers bringing drinks, including soda, which can worsen dehydration. Moving forward, access to “cool, palatable water is not negotiable,” Campbell Harris emphasized.

Changing behaviors is never easy. And while “you can’t make anyone do anything,” Campbell Harris added, it’s the responsibility of employers to implement the new standards and foster a workplace culture that prioritizes safety.

Communication is Key

Effective implementation depends on clear communication. The law requires employers to provide training and materials in the workers’ native language. MOSH confirmed that Spanish-language versions of the regulation, key requirements and summaries are in development and will soon be available on the agency’s website.

“We anticipate these materials will be posted soon,” MOSH said in a statement to our team. “We will continue to take steps to ensure that both workers and employers are well-equipped to identify and address risks resulting from occupational exposure to heat before temperatures rise.”

However, many of our participants also speak Haitian-Creole, not just Spanish. And posting materials after the spring harvest season has begun isn’t enough. Heat index values in Salisbury have already surpassed 80°F in April.

To be effective, we believe training must be:

Timely to prepare workers before temperatures surpass 80°F

Culturally tailored and delivered by trusted messengers

Framed around preventing illness and reducing lost workdays

Supported by third-party trainers when needed

Designed with employees and employers in mind, many of whom only speak English

Next Steps and Uncertain Futures

Maryland’s heat stress standard arrives at a critical moment as temperatures and political tensions rise. Federal efforts to establish a national heat standard stalled under the Trump administration, leaving an estimated 36 million U.S. workers vulnerable to heat exposure.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration recently scheduled an informal public hearing for June 16, 2025, to revisit a national heat rule. But both that timeline and the policy itself remain uncertain.

In the meantime, state-level protections, however imperfect, are essential.

Still, without robust outreach, funding for enforcement and culturally competent infrastructure, Maryland’s trailblazing policy risks becoming an under-enforced mandate. And that could mean another blazing summer without meaningful protection for the people who need it most.